Recovering Nix derivation attributes of runtime dependencies

October 8, 2019

A coworker recently asked me to compile a list of licenses used at runtime by

some of our build products. Most nixpkgs derivations have a bunch of metadata

associated with them, why not use that? Turns out it’s not that trivial.

It’s nothing ground breaking, but was a pretty nice puzzle to crack. Let’s get started!

You can find the full code as a gist.

Tonight’s Program

The idea here is that we want to use the original derivation object (for

instance the meta field) of packages that are depended on at runtime.

That means you can generate a “runtime report” like this:

let

pkgs = import <nixpkgs> {};

runtimeReport = ... ;

in runtimeReport pkgs.helloand that’d give us:

---------------------------------

| OFFICIAL REPORT |

| requested by: the lawyers |

| written by: yours truly |

| TOP SECRET - TOP SECRET |

---------------------------------

runtime dependencies of hello-2.10:

- glibc-2.27 (lgpl2Plus) maintained by Eelco Dolstra

- hello-2.10 (gpl3Plus) maintained by Eelco Dolstra

This is the “runtime report”, i.e. what you’ll be sending to your lawyers, your boss, your mom, anybody who can enjoy a good runtime report. It consists of a few “dependency reports” which (in this example) contain information about runtime dependencies:

-<name>(<license>) maintained byEelco Dolstra<maintainer>

Now let’s talk about how this works. The “runtime report” is created in two steps:

- Generate reports for all the buildtime dependencies with

buildtimeReports. - Filter out the reports for buildtime-only dependencies.

We’re using the following terminology:

- “buildtime” to mean basically any derivation involved in the build of

drv. - “buildtime-only” for the “buildtime” dependencies that are not

referenced anymore by

drv’s store entry. - “runtime” for the rest.

Most of the “buildtime” reports won’t even be used, because most buildtime dependencies are buildtime-only dependencies. Why generate them? Nix does not give us a way of retrieving the derivation attributes of runtime dependencies, but we can twist its arm to:

- Give us the store paths of runtime dependencies.

- Give us the derivation attributes of all the buildtime dependencies.

Here’s the hack: when going through the buildtime dependencies, we tag them with their (expected) store paths, which we then cross check against the list of runtime store paths. If it’s a match, we keep it. Otherwise, we discard it.

Let’s look at some code. We’ll go top-down, starting with the function creating the final string.

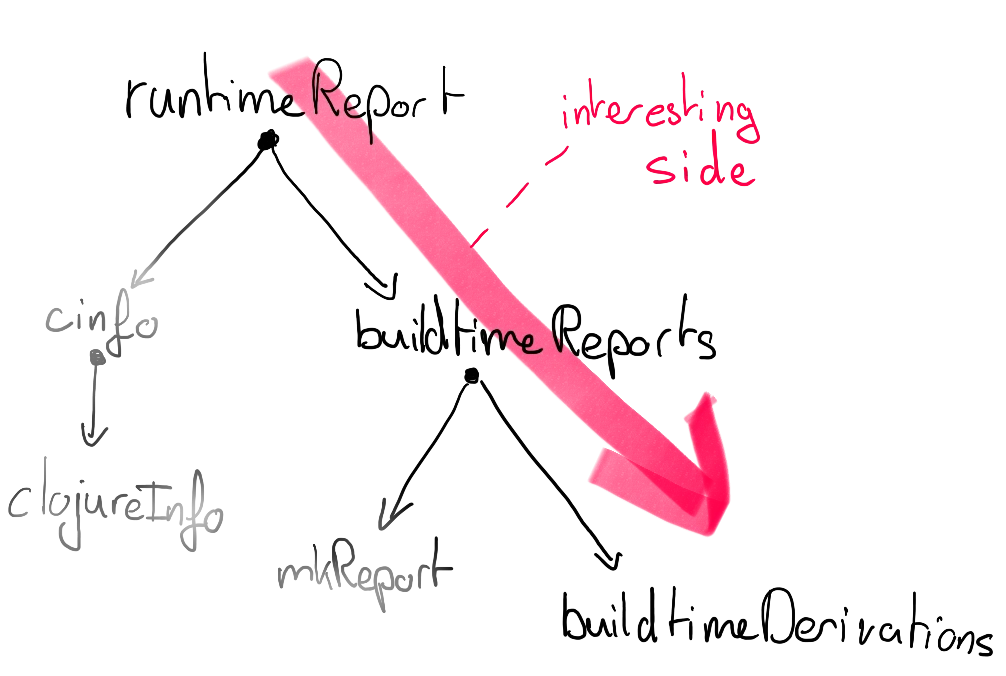

The “Function Tree”. Today we’ll follow the red arrow.

It’s Showtime

I hope you like jq:

runtimeReport = drv:

runCommandNoCC "${drv.name}-report" { buildInputs = [ jq ]; }

''

(

echo " ---------------------------------"

echo " | OFFICIAL REPORT |"

echo " | requested by: the lawyers |"

echo " | written by: yours truly |"

echo " | TOP SECRET - TOP SECRET |"

echo " ---------------------------------"

echo

echo "runtime dependencies of ${drv.name}:"

cat ${buildtimeReports drv} |\

jq -r --slurpfile runtime ${cinfo drv} \

' # First, we strip away (path-)duplicates.

unique_by(.path)

# Then we map over each build-time derivation and use `select()`

# to keep only the ones that show up in $runtime

| map( # this little beauty checks if "obj.path" is in "runtime"

select(. as $obj | $runtime | any(.[] | . == $obj.path))

| .report)

| .[]'

) > $out

'';The most important thing to notice here is the absolutely delicious argument

name slurpfile. Once you get over that, and if you look at it long enough,

you can convince yourself that this function doesn’t do much: it prints the

record field of all the objects in buildtimeReports, as long as those

objects have a path that is found in cinfo. You guessed right: cinfo are

the paths of the runtime dependencies, and builtimeReports are… the

buildtimeReports.

We’re not going to discuss cinfo much. It’s a wrapper around closureInfo,

which itself is a helper for using exportReferencesGraph, which …

basically, cinfo gives you the list of store paths used (or referenced) at

runtime.

Instead let’s look at buildtimeReports, which creates reports for all of

drv’s buildtime dependencies. Each element in the resulting list has two

fields:

- path =

"/nix/store/..." - report = “some report based on the dependency’s derivation attributes”

The path is the store path of the dependency, and report is where you can

go crazy:

buildtimeReports = drv: writeText "${drv.name}-runtime" ( toJSON (

map (obj:

{ path = unsafeDiscardStringContext obj.key;

report = mkReport obj.drv;

}

)

(buildtimeDerivations drv)

));

mkReport = drv: "something interesting with ${drv.meta}, although it will most likely mention Eelco or peti";blah blah blah something about

unsafeDiscardStringContextblah blah blah

I know, right!?! My cat jumped on my keyboard and somehow typed that in! I

thought it was gonna break everything but it didn’t, instead it just super sped

up the build when downloading from the binary cache! I really love my cat, I

can blame anything on it it cares about the size of my /nix/store!

This function grabs the buildtimeDerivations and creates a report for each.

It also tags those derivations with their path which, as we’ll see in a second,

is stored in the object’s .key (whereas the derivation itself is in .drv).

Build-time derivation objects

Getting the paths of runtime dependencies — that we got for free from cinfo.

As we walk down the tree of functions, we get to the other big piece of the

puzzle: laying our hands on the original derivations of all the buildtime

dependencies.

My cat is responsible for this drawing as well.

This one’s called buildtimeDerivations and does something very simple. It

takes the original derivation object (e.g. pkgs.hello) and goes through all

the attributes. Whenever you hit another derivation (for instance from

buildInputs), put it in your backpack, and continue. Once you’ve found them

all, open your backpack and recurse into all your newly found derivations, ad

nauseam.

There are no guarantees that this will find all inputs, but it works well enough in practice:

buildtimeDerivations = drv0:

let

drvDeps = attrs: ...; # recurses into the attrs to find other derivations

in

let wrap = drv: { key = drv.outPath ; inherit drv; }; in genericClosure

{ startSet = map wrap (drvOutputs drv0) ;

operator = obj: map wrap

( concatLists (drvDeps obj.drv.drvAttrs) ) ;

};The safest, and probably fastest way to traverse a graph in Nix is

genericClosure. Give it a startSet, an operator to generate new nodes

from the current node, and you’ve got yourself a full traversal. What’s a

“node”? It’s anything that has a key field. Here we use drv.outPath as the

key, and it should now be clear where the key came from in

buildtimeReports.

And just like that, we’ve reached the bottom of the function tree. Let’s grab our ladder, go back up and look at the bigger picture.

IFD vs jq-galore

By far the most frightening piece of code today was:

unique_by(.path) | map(select(. as $obj | $runtime | any(.[] | . == $obj.path))| .report)| .[]Don’t remember seeing it? That’s “selective memory”. Probably took me a full hour to come up with it.

Given that Nix has readFile and fromJSON, we could have lifted cinfo’s

output to a Nix value, then performed all the matching on that value, and

generated the report as a Nix string directly! Added bonus, the

“buildtime-only” reports would never have been generated, thanks to laziness!

The problem from readFile-ing cinfo is … import from derivation. I stay

away from it, but YMMV, try it! Leave your thoughts in the comment section

below.

..--""|

| |

| .---'

(\-.--| |-----------.

/ \) \ | | \

|:. | | | |

|:. | |o| >/dev/null |

|:. | `"` |

|:. |_ __ __ _ __ /

`""""`""""|=`|"""""""`

|=_|

|= |

I lied, there’s no comment section. Artwork by Joan G. Stark.

Let me know if you enjoyed this article! You can also subscribe to receive updates.

Here's more on the topic of Nix and build systems: