Puzzle solving in Haskell

July 31, 2016

In order to warm up for a round of interviews next week, I’ve been playing around with coding puzzles. Those are usually solved using imperative languages, and I thought I’d have a go at them using Haskell. I’ll share today’s experience, which hopefully will convince you that purely functional languages are (sometimes) suitable for puzzles.

Disclaimer

There is probably nothing new here. Also, there might be better solutions to solve the problem. I like this solution because it gave me an excuse to showcase Haskell’s laziness. Feel free to ping me if you come up with something better.

The puzzle

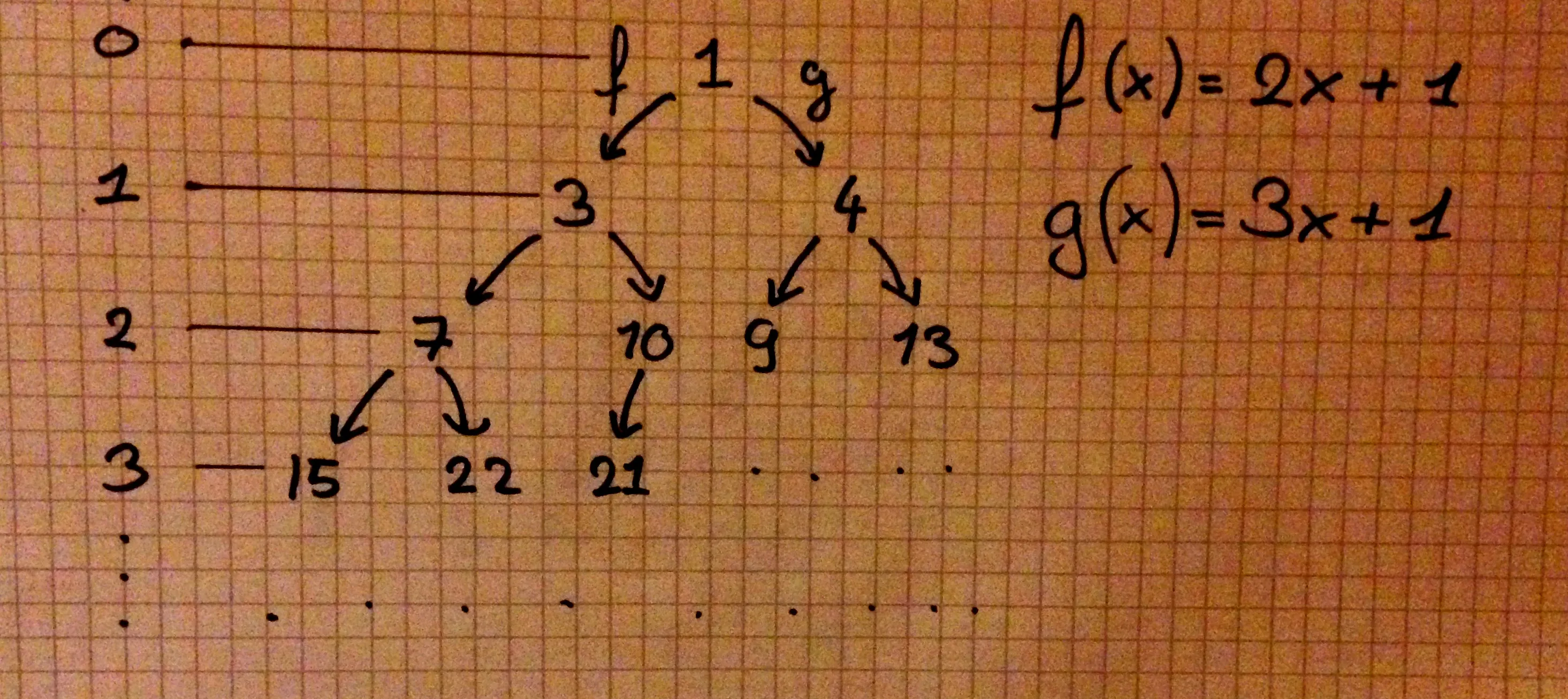

Let’s start with the problem itself. You are given a number, , and a target, . You are allowed two functions: and

Give either the minimal number of applications of and that you need in order to reach from , or state that one cannot reach from .

For instance:

-

in order to reach from , you need one application:

-

in order to reach from , you need two applications:

-

you cannot reach from .

I like to think of the values as a tree where each node has degree . To get to a left child, apply . To get to a right child, apply . In this case the answer is equal to the depth of , where the root is . Now you just need to traverse the tree, starting from the root, until you find . Using the following observation:

we know that we can safely stop whenever we hit a node with depth:

.

Clearly the number of nodes traversed (assuming a BFS) is proportional to the exponential of the depth (it is actually ). But we also know that there is at least a factor between each “layer” (). So we can conclude that and so our algorithm should run in . Now let’s write some code.

The code

import System.Environment (getArgs)First we need to define a suitable tree structure. We define a binary tree in which each node holds some data. The data we will record is the node’s depth (or distance from the root) and a value:

data Tree = T { depth :: !Int

, value :: !Int

, l :: Tree

, r :: Tree }We keep the links to the children lazy so that we can build an infinite

tree. Whenever we create a node it is very likely that we will need the

data it contains, so we keep the data strict. This is a typical lazy

spine/strict leaves structure, and has the added bonus of easily

allowing GHC to unpack the Ints.

Now, let’s build that tree:

mkTree :: Int -> Tree

mkTree = go 0

where

go d v = T { depth = d

, value = v

, l = go (d + 1) (2 * v + 1)

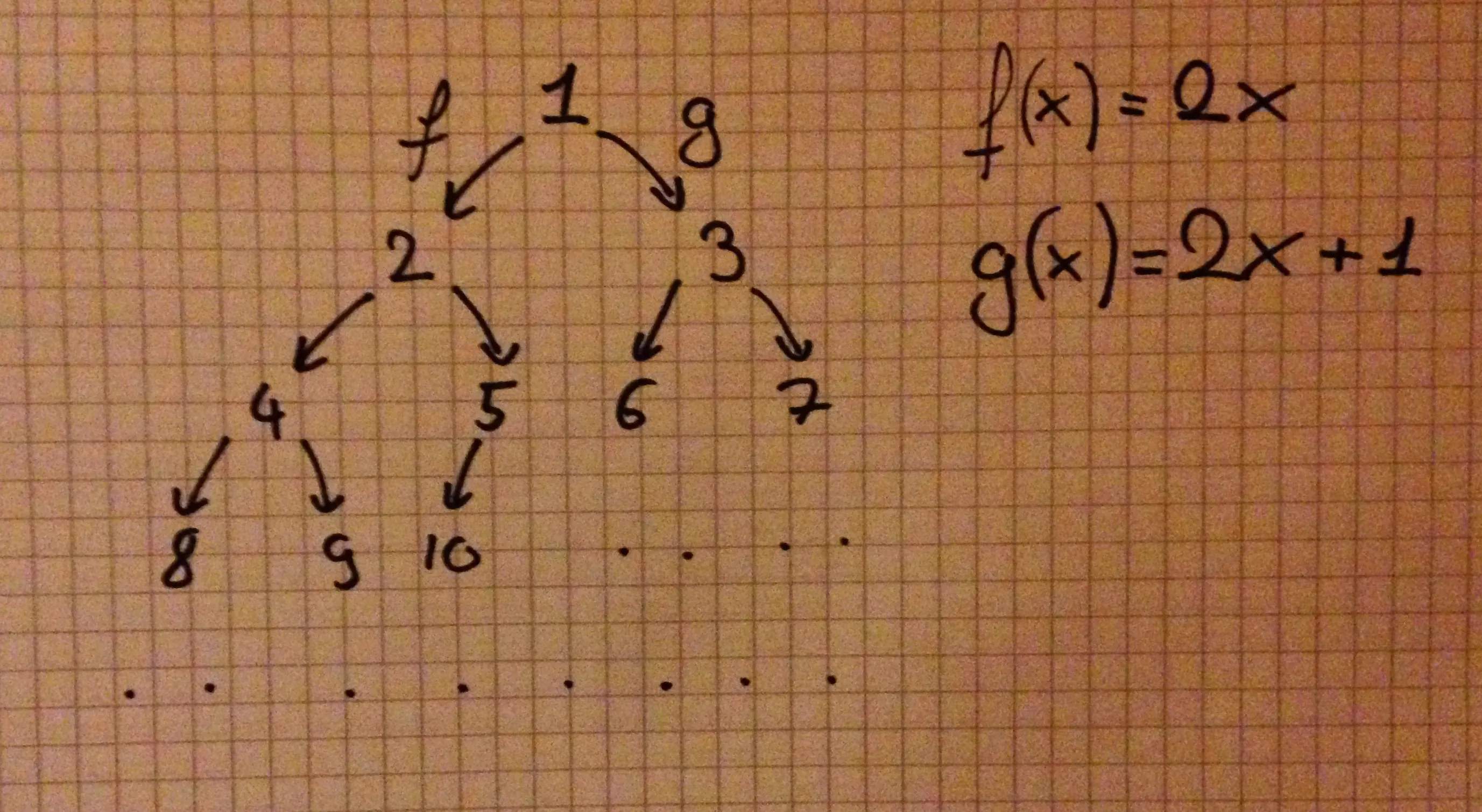

, r = go (d + 1) (3 * v + 1) }Note that we don’t have to limit ourselves to the functions and . Here’s, for instance, a complete binary tree:

-- As an example

completeBinaryTree :: Tree

completeBinaryTree = go 0 1

where

go d v = T { depth = d

, value = v

, l = go (d + 1) (2 * v )

, r = go (d + 1) (2 * v + 1) }This second tree would look like this:

Now comes the fun part, the breadth-first search (note that you typically don’t want to do a depth-first on an infinite tree). A typical implementation of a BFS uses a queue. It would go something like this:

- Dequeue a node from the queue and append it to an output list.

- Enqueue all this node’s children.

- Repeat until your queue is empty.

This is a simplified version that will work just fine for a tree (we don’t need to check whether or not we have already visited the current node). If you know your functional data structures, you’ll recognize a typical queue:

data Queue a = Queue { front :: [a]

, back :: [a] }Whenever you want to enqueue a value, you cons it on back. Whenever

you want to dequeue a value, you uncons it from front. And whenever

front is empty you replace it with back (in reverse order). This gives

you worst-case O(1) for enqueue and dequeue operations, and O(n) for

tail (that’s where you’ll reverse the back, see Okasaki’s Purely

Functional Data

Structures for a good

overview).

The search

Easy enough. Now we just need a State Queue monad, traverse the tree,

and update our queue every time, discarding the old one. Also, we’ll

need a Writer [Tree] to output the nodes. Right? Well, in our case we

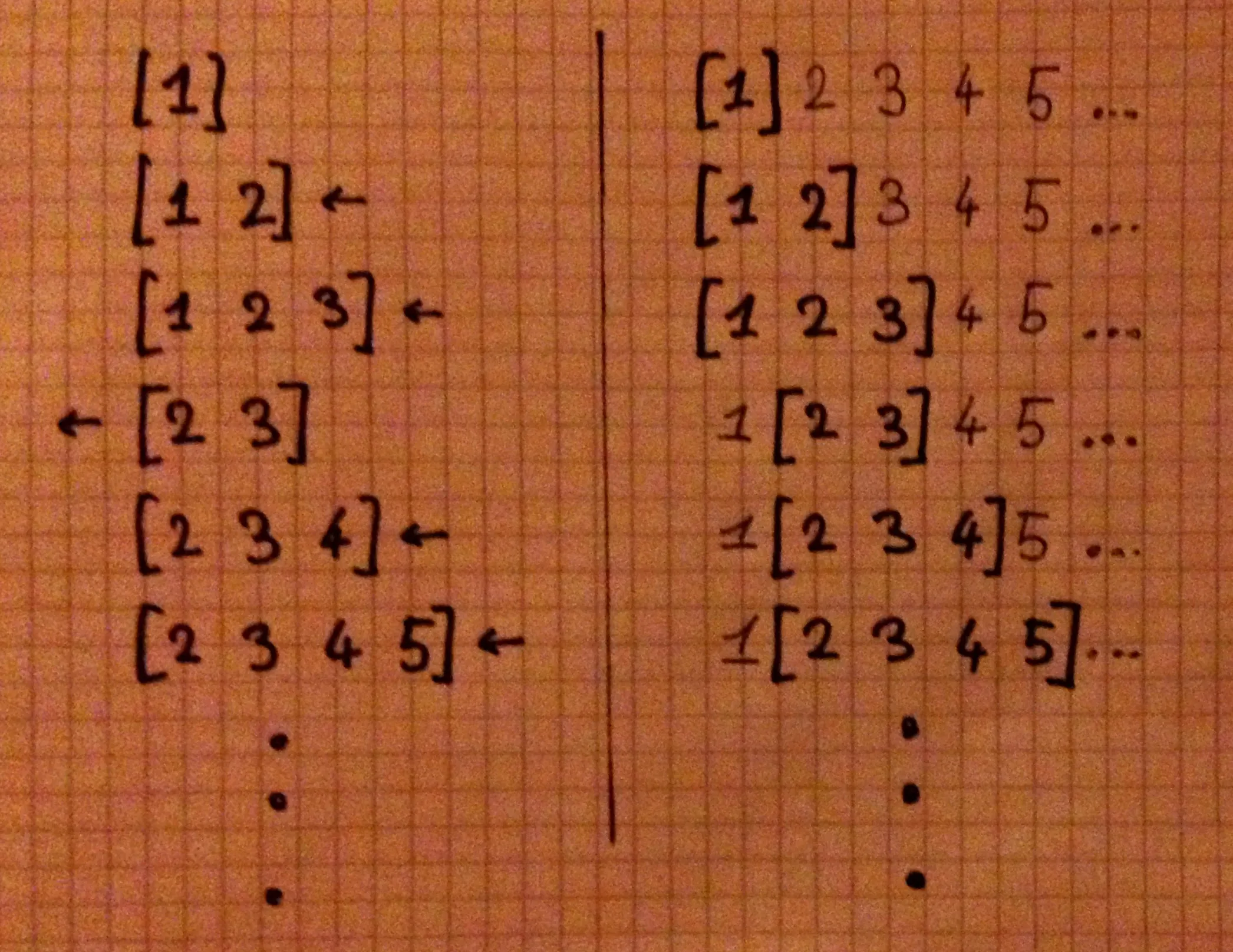

can do much simpler. We will simply use a list and take advantage of the

language’s laziness. We’ll take a list of nodes and return a list of

their children. It will extract the left and right children of a node,

then move to the next node, repeat the process and concat the result.

children = concatMap (\t -> [l t, r t]) nodesAll good. Now we just need to bootstrap it:

bfs :: Tree -> [Tree]

bfs root =

let

nodes = root : children

children = concatMap (\t -> [l t, r t]) nodes

in nodesLet’s check it out on our binary tree in ghci:

λ: value <$> take 10 (bfs completeBinaryTree)

[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]Sweet! When concatMap is called the first time, it’ll split the root

into its left and right children. This means that the root’s left child

is now the second element in nodes. When concatMap has to work

again, it’ll spit out first the left child’s own children, then the

right child’s own children, etc, concating the children lists every

time. Looks like we have a breadth-first search using a list instead of

a queue! And added bonus, we got rid of Queue’s O(n) worst case,

since we never even tail!

In this case, a queue is nothing more than a window, or slice, of a list. Every time we enqueue, we expand the window to the right. Every time we dequeue, we shrink the window on the left. This is unfortunately not an all purpose queue. Once the first cell of the list is created, all the remaining ones must be determined already.

The only thing left to do is to traverse the nodes produced by bfs

until we hit either or a number that we know is too large:

distance :: Int -> Int -> Maybe Int

distance x0 xf = go nodes

where

nodes = bfs $ mkTree x0

go (t:ts) | value t == xf = Just $ depth t

| value t > 4 * xf = Nothing -- from analysis

| otherwise = go tsEt voilà! We can go a bit fancy and add a cli (that will happily crash on you on bad input):

main :: IO ()

main = do

[x0, xf] <- (read <$>) <$> getArgs

print $ distance x0 xfCompiled with

$ ghc --make -O2 -funbox-strict-fields bfs-tree.lhsthe program runs to up to 10,000,000,000 under two seconds, which is not too bad. (Dell XPS 13, 2015)

$ time posts/2016-07-31-bfs-tree 1 3000000000

Nothing

posts/2016-07-31-bfs-tree 1 3000000000 0.57s user 0.13s system 99% cpu 0.708 total

$time posts/2016-07-31-bfs-tree 1 6000000000

Nothing

posts/2016-07-31-bfs-tree 1 6000000000 1.04s user 0.19s system 99% cpu 1.230 total

$ time posts/2016-07-31-bfs-tree 1 10000000000

Nothing

posts/2016-07-31-bfs-tree 1 10000000000 1.49s user 0.62s system 99% cpu 2.111 totalTo get it to run on larger inputs, I suspect one would need to find a

better algorithm. It would maybe even allow replacing Ints with

Integers. Once again, if you do find something, please get in touch :

)

Let me know if you enjoyed this article! You can also subscribe to receive updates.