Stutter: the anti-grep

May 1, 2017

I’m going to introduce stutter, a

command line tool for generating strings. I’ll first show some examples, then

talk a bit about the performance and finally about the implementation (for the

Haskell friendly reader).

This short introduction was motivated by a recent post on reddit where the author was looking for something similar (though packaged as a library).

Examples

In its essence, stutter does the opposite of what grep does. You pass

grep a definition string and it will find all the matches in the input you

provide it. You pass stutter a definition string and it will generate an

output based on that string:

$ echo 'foo\nbar\nbaz' | grep -E 'foo|bar|baz' foo bar baz $ stutter 'foo|bar|baz' foo bar baz

The most basic usage would be to use stutter as an echo clone:

$ echo 'foo' foo $ stutter 'foo' foo

Though stutter will go further, and allow you to define the output strings in

various ways. For instance, you might want either foo or bar. You can use

the sum operator | as in the following snippet:

$ stutter 'foo|bar' foo bar

Both foo and bar will appear, but not together. To go back to the first

example, let’s simply drop echo so we can better see the parallel between

grep and stutter:

$ stutter 'foo|bar|baz' | grep -E 'foo|bar|baz' foo bar baz

There is an equivalent product operator # if you need both foo and bar:

$ stutter 'foo#bar' foobar

In this example you could have simply run stutter 'foobar' to get the same

result, but sometimes the # operator can come in handy (see for instance the

fold operator {|} in the readme’s

examples). Let’s see another

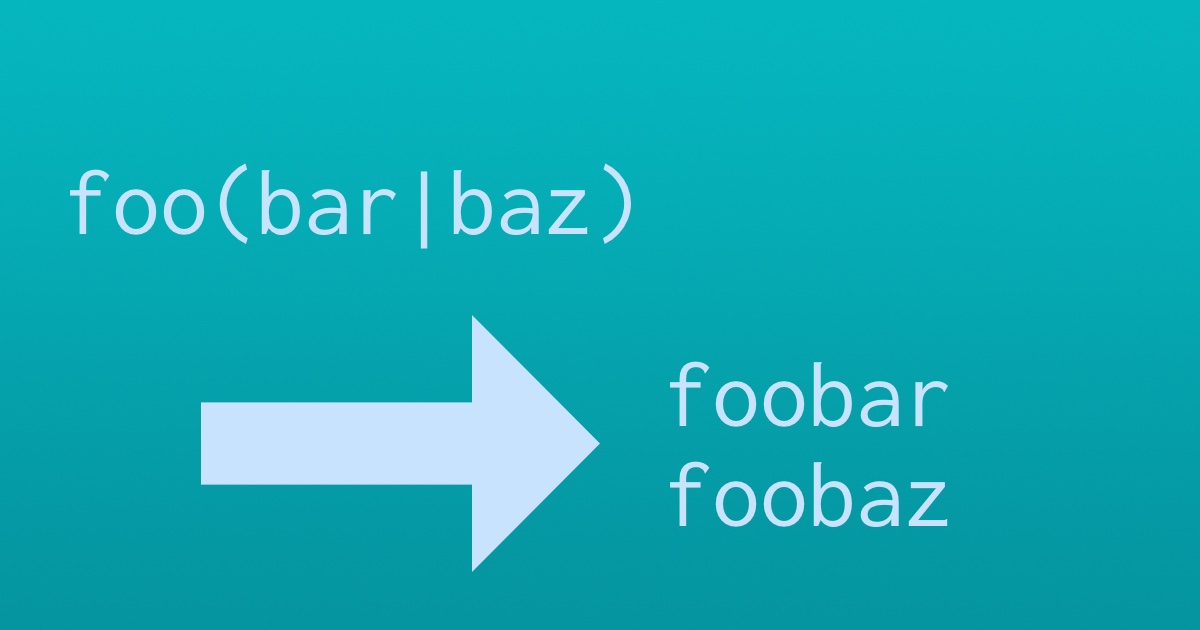

important construct, namely the grouping operator (). Say you want either

foo and bar or foo and baz:

$ stutter 'foo(bar|baz)' foobar foobaz

Two things to notice:

- The

()operator is optional for groups of one element. It was not necessary to write(foo)(bar|baz).stutterwill assume a group is ending on the first operator occurrence. If you need to use operator characters, you can escape them with a backslash (\) character. - The

#operator is used by default when no other operator is found. It was not necessary to writefoo#(bar|baz).

There are more examples in the stutter

readme showcasing things like

repetition, sourcing files and stdin, character ranges, and more.

Performance

As much as possible stutter tries to only use constant memory. The heap

should never grow as long as you stick to “pure” string generations, even if

you perform products of infinite lists of words. However the situation is

different with “unpure” string generation, for instance when sourcing words

from stdin. stutter will do its best to keep the memory usage low. The

following for instance will zip stdin with itself:

$ cat some_big_file line001 line002 line003 ... $ cat some_big_file | stutter '(@-)$(@-)' line001line001 line002line002 line003line003 ...

The zip operator $ will zip two outputs together, and the @- group will be

replaced by the content read from stdin. The example above will still run in

constant space, because stutter realizes that it can discard a line from

stdin as soon as it was printed. The situation is different with products:

$ cat some_big_file | stutter '(@-)#(@-)' line001line001 line001line002 line001line003 ... line002line001 line002line002 line002line003 ...

Here stutter must keep the entirety of the group to the right of the

product operator #, because it will be repeated for each element produced by

the group to the left of the operator. The reason is that stutter cannot tell

stdin to simply “rewind” and start again from the beginning of the input.

However, consider the slightly different example:

$ stutter '(@some_big_file)#(@some_big_file)' ...

This command produces the exact same output, but reads some_big_file

directly. In this case stutter will prefer reading the file from disk over

and over again rather than keeping it in memory. This is something you should

keep in mind if your operation has to perform many disk reads and that your

hard-drive is slow. If the live data is not too big consider threading it

through stdin first (I might add an option to enable the behavior when

reading from a file).

For most operations stutter should outperform commands composed from several

different programs and shell built-ins. The reason is that stutter runs in a

single process (which avoids context switches and inter-process communication),

and that stutter is optimized for specific kinds of commands. For instance on

my machine printing the a character to stdout a million times takes over

three seconds with echo while it only takes half a second with stutter:

$ time (stutter 'a+' | head -n 1000000 | wc -l) 1000000 ( stutter 'a+' | head -n 1000000 | wc -l; ) ⤶ 0.62s user 0.13s system 145% cpu 0.515 total $ time (while true; do echo 'a'; done | head -n 1000000 | wc -l) 1000000 ( while true; do; echo 'a'; done | head -n 1000000 | wc -l; ) ⤶ 2.32s user 3.32s system 154% cpu 3.658 total

Implementation

The stutter code is spread across two tiny modules and is basically a thin

wrapper around the excellent

conduit library. The first

module,

Stutter.Parser,

is dedicated to parsing the commands. The only exported function is

parseGroup:

parseGroup :: Atto.Parser ProducerGroup parseGroup = ...

From a command input by the user stutter will try to extract a

ProducerGroup,

which is a tree-like data-structure defined in the second module,

Stutter.Producer.

The role of ProducerGroup is that of an AST:

data ProducerGroup_ a = PSum (ProducerGroup_ a) (ProducerGroup_ a) | PProduct (ProducerGroup_ a) (ProducerGroup_ a) | PZip (ProducerGroup_ a) (ProducerGroup_ a) | PRepeat (ProducerGroup_ a) | PRanges [Range] | PFile FilePath | PStdin a | PText T.Text deriving (Eq, Show, Functor, Foldable, Traversable)

The meat of stutter is in the

produceGroup

function, also defined in Stutter.Producer. This turns a parsed

ProducerGroup into a conduit

Source:

produceGroup :: (MonadIO m, MonadResource m) => ProducerGroup -> Source m T.Text ... produceGroup (PZip g g') = zipSources (produceGroup g) (produceGroup g') .| CL.map (uncurry (<>)) ...

If you look through the code you will see that produceGroup doesn’t do

anything fancy, it just leverages the conduit capabilities.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this quick introduction to

stutter and that, one day, it might

help you do your job faster (like for instance recovering a forgotten

password). Please read

the contributing section

of the README, there’s a lot you can do to help the development and improve

stutter, the anti-grep.

Let me know if you enjoyed this article and report an issue if something doesn't look right!

Like Haskell? Here's more on the topic: